The success story of falling costs…

In 2010, Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte told an audience that ‘those silly wind turbines don’t run on wind but on subsidies’. Only eight years later his government announced that offshore wind should make up 40% of Dutch electricity production by 2030. What made this remarkable shift in perspective possible was a dramatic reduction in the cost of offshore wind across the North Sea region from €150 per megawatt-hour in 2013-2015 to about €50 in 2019.1 Rapidly increasing turbine size and other technological innovations drove down costs rapidly. Up to around 2015, each turbine had a generation capacity of 3 Megawatt (MW), while just a couple of years later turbines of 8 MW each were tendered. Another major factor were well-designed government tenders, delivered as ‘package deals’ with locations, environmental studies, permits and grid-connections all pre-arranged. In countries like Germany and the Netherlands this led to subsidy-free offshore wind.

…Turning the tide of rising costs

Recently however, the era of low-cost offshore wind seems to have come at an end. The latest UK auction round failed because not a single investor handed in a bid. Several large projects have been cancelled internationally as costs of turbines and installation increased as inflation soared and borrowing costs increased. High electricity prices were a feast for operational wind farms in the last two years, however also reduced the appetite in industry to switch their processes from gas to electricity. This led, together with falling electricity demand, to uncertainty for wind farm investors about future revenues.

Offshore wind is crucial, not just to the energy transition, but also to our own energy freedom through increasing domestic production. So what can be done to turn the tide and ensure a positive business case? Both governments and the offshore wind sector can play their part.

Profitable wind farms save us money

In the long-term, offshore wind’s success will benefit from gradually increasing carbon prices which will drive up electricity demand because it will incentivise the industry, transport and building sectors to shift from fossil fuels to renewable electricity. In the short term, governments can opt for smart ways to support the business case for offshore wind. One example is a new European electricity market policy which will allow for an innovative support mechanism that would provide certainty to investors, lowering risks and borrowing rates. How could it work?

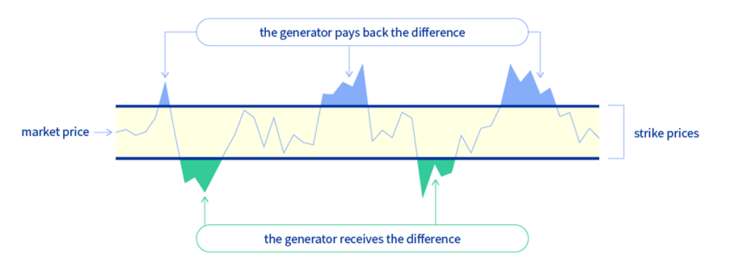

Europe suggests so-called two-way contracts for differences (CfDs) with the option to include multiple strike prices. A CfD mechanism incentivises investment in energy production assets with a high upfront cost, by providing stable prices over a long period. In the context of renewable energy, it offers subsidies when market prices are low, but requires investors to make a payback if market prices go above a level predefined by government. This offers certainty to investors while also avoiding excessive revenues. Such CfDs are used already in the UK. A multiple strike price CfD takes it one step-further. It involves setting a lower strike price for receiving subsidies, and a higher one for government clawback, which can be passed on to consumers. Such an approach offers more space to the market and encourages investors to minimise costs to enjoy the greatest profits.

Source: European Council 2023

But investors can play their part too in enhancing the business case. In the future, wind power will also be used to produce hydrogen. This offers wind farm operators the opportunity to produce hydrogen at times of low electricity prices and sell electricity when prices are high. In the short term, the sector can embrace standardisation. Counterintuitively, technology innovation now reduces cost-efficiency, since the wind sector is pushed to produce larger turbines every couple of years, each time requiring new logistics chains to produce, deliver, install and maintain them. The history of shipping containers offers an example. In the 1960s, shipping container sizes were united to the TEU standard which saw costs drop from $6 per ton to just 16 cents. Similarly, standardisation of wind turbine size would reduce the need for new investments in vessels, harbours, workforce training and more. This would reduce costs and waste, as components no longer require constant upgrades. The Dutch Wind Energy Association recently proposed a standard for 1000-feet high turbines. It would be helpful for the sector to embrace it.2

1 Offshore wind competitiveness in mature markets without subsidy | Nature Energy

Shape common futures together with us

Get in contact