(First published as an op-ed in Recharge News, 2 October 2025)

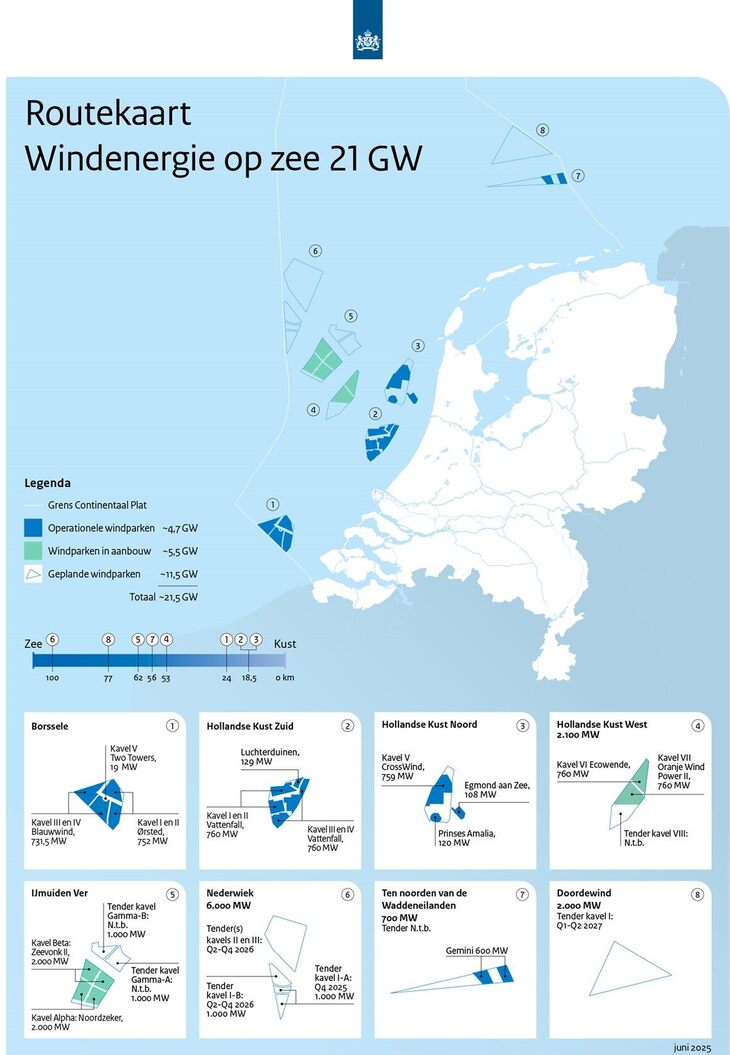

The Dutch offshore wind programme is in trouble. While 4.5GW is in operation and another 1.5 GW under construction, the original plan was to rapidly build out capacity to 21GW by 2032. That target is now out of reach. Stagnating electrification combined with the rising cost of offshore wind turbines have made developing and building offshore wind farms less attractive, and the Netherlands has now as reached a point where integrated policy support on demand creation, infrastructure, and offshore wind is necessary to put the programme back on track.

Ambitious targets, faltering progress

Five years ago, things looked very different. In 2021, driven by the rapid cost reductions in an ongoing 3.5GW scheme, the Dutch Parliament asked the minister of Economic Affairs and Climate to come up with an accelerated plan for 21GW of offshore wind by 2030. The offshore wind industry confirmed that this would be possible provided that the planned electrification of industry created rising demand. But it soon became clear that building the necessary grid infrastructure would take more time than expected, and the target year was postponed to 2032.

However, the expected increase in demand did not happen. Industry in the Netherlands – as across Europe - had to cope with high energy prices related to Russia’s attack on Ukraine. And as investments in electricity grids – both onshore and offshore – increased, so did grid fees, further reducing industry’s own appetite to invest in electrification.

While politicians had hoped that the era of subsidy-free offshore wind farms would be here to stay, and developers might even pay for their concessions, the tables turned and interest in Dutch tenders declined. In the last round, only two bids were received for each of the 2GW lots.

Another 1GW will be tendered this fall, and 2GW next year. If this capacity gets built, it will still only bring us to 13GW by 2032, and even that is not a certainty.

The government has already acknowledged the need to reintroduce subsidies, and is considering a Contract for Difference (CfD) scheme for future tender rounds.

That means the new coalition government that is likely to emerge from elections on 29 October would have to tender at least 8GW in 2027 to have the target capacity ready by 2032. This is an unprecedented amount, and too much to handle in one year. But grid operator TenneT has already ordered the HVDC platforms and cables to connect 21GW, so if this capacity does not materialise by 2032, there will be substantial delay costs.

Creating demand through electrification, storage and flexibility

Any big tender volume in 2027 and beyond would require a solid outlook on growing electricity demand from heating buildings, powering electric vehicles and, most of all, industry. Government has taken a step in this direction by signing a letter of intent with Tata Steel, including substantial support for its investment in an electric arc furnace as part of a transition to producing steel via direct reduction of iron.

Another avenue is ‘demand creation’: at the end of a value chain the additional cost of renewable energy becomes a minor part of the product price for a consumer. A car produced with renewable energy is just a few hundred euros more expensive than one produced with fossil fuel energy. If consumers are prepared to pay a premium, this generates demand upstream in the value chain.

In every credible energy scenario for northwest Europe, offshore wind – as a major zero-emission, domestic source of renewable energy - is an essential part of the future system.

For our energy balance, we will need so much capacity that its production exceeds direct electricity demand in high-wind periods. To make optimal use of the energy produced, storage and flexibility in the system are required: batteries, electrolysis, hydrogen storage, demand response and stronger interconnections across Europe. So while straightforward demand growth by electrification will help to get offshore wind out of the doldrums in the coming years, much more is needed to unleash its full potential.

A complex balancing act for policymakers

The challenge is complicated, balancing offshore wind, electrification, and required infrastructure and flexibility, not only in an ‘end state’ but also during the transition.

Addressing this will requires solid government direction, driven by a strong sense of urgency on energy and climate, and in close cooperation with the countries around the North Sea.

Kees van der Leun is energy system consultant and managing director at Common Futures. He has advised major offshore wind developers on energy system integration matters and the Dutch government on its North Sea Wind Energy Infrastructure Plan.

Shape common futures together with us

Get in contact